Another fantastic article in the

Carmel Valley News highlighting the work that continues in the fight against neuroblastoma, and not only in San Diego, not only in Vermont, but across the country. Parents both working together and on their own are doing amazing things, including the

Band of Parents ,

Ishan Gala Foundation ,

Friends of Will , and or course my old home,

Magic Water , which continues (as it should) despite my leaving to focus on

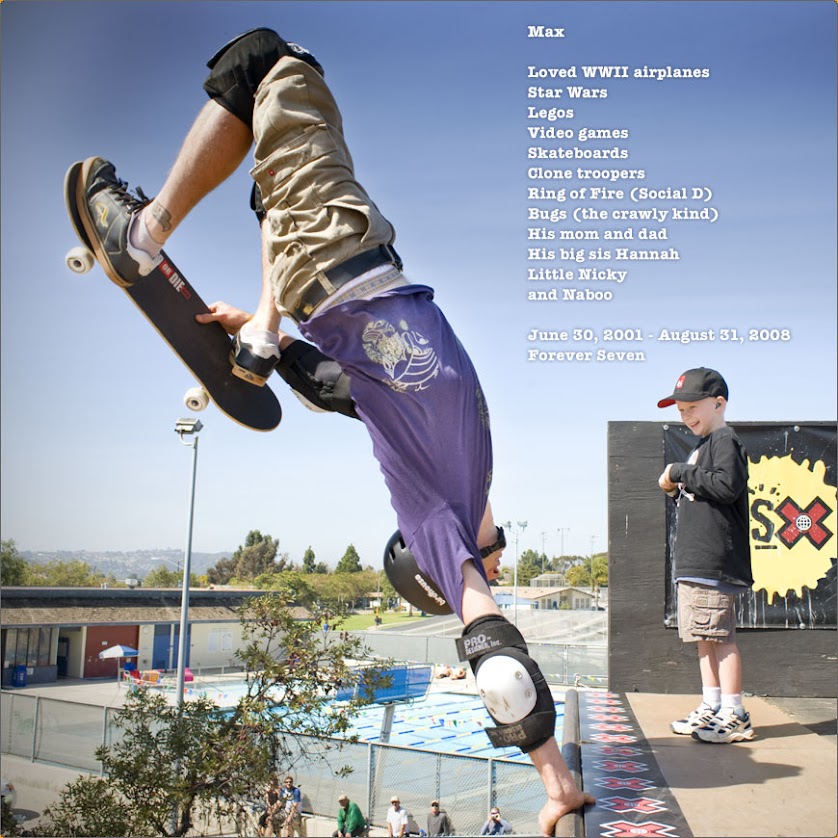

Max's Ring of Fire. Please take a moment to visit the websites listed above and learn more about what everyone is doing, in an amazingly uncoordinated but still synchronized focus of effort to push for the research and clinical application of therapies that will turn this killer into something benign. Post their URLs on your blog, facebook, etc to help spread the word and THANKS for continuing to come here and help remember Max along with us.

Max Mikulak’s father backs new alliance of pediatric doctors, researchers dedicated to finding cure for fatal disease.

By Catherine KolonkoA Carmel Valley father who lost his son to relapsed neuroblastoma last year is championing a group of doctors dedicated to finding a cure for the fatal disease.

A new alliance of pediatric doctors and researchers in San Diego and across the United States are pooling resources to conduct multi-site clinical trials to test new treatments for children whose lives are at stake. Like Max Mikulak, a popular 7-year-old Carmel Valley boy who died last August, time is running out for these children because there is currently no known cure for relapsed neuroblastoma, a type of pediatric brain cancer that is diagnosed in about 600 children per year in the United States and has only a 30 percent survival rate.

Almost 80 percent of children with cancer become long-term survivors, but then there are 20 percent that don’t, according to

Dr. William Roberts , an oncologist at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego who treated Max’s cancer. For children with relapsed neuroblastoma the outlook has been bleak.

Doctors and families fighting the disease share a frustration that while there are drugs that if tested might work for these children there is no business reason to pursue them. The approved treatment options are limited just because of the relatively small number of children affected by the deadly cancer.

This has culminated in the formation of a new clinical trials consortium, the TRC or Translational Research Consortium, with San Diego functioning as one of the four core sites, the others being Vermont, St. Louis, Mo., and Houston. Having more sites geographically situated throughout the United States should ease the burden of families with sick children who must travel to seek care for them.

Roberts said the consortium will allow doctors caring for children with neuroblastoma to compare treatments and diseases on a larger scale. The idea, which is not new but has proven beneficial, is to feed data to a central data base. “In one center we may see six to 10 kinds of neruoblastoma per year,” he said. But pooling efforts “allows us to learn much more rapidly.”

Neuroblastoma is an aggressive disease in which malignant cancer cells form in nerve tissue of the adrenal gland, neck, chest, or spinal cord. By the time it is diagnosed, the cancer has usually metastasized most often to the lymph nodes, bones, bone marrow, liver and skin, according to the National Cancer Institute. Usual treatment options involve high doses of chemotherapy, radiation and stem cell transplant.

One of the doctors participating in the consortium,

Giselle Sholler, of the University of Vermont , said she and others involved with the alliance came together in San Diego last month to begin the process of forming the consortium. They recently held their first conference call to discuss the plans for future clinical trials.

“We mapped out five other trials we want to get started this year,” Sholler said in a telephone interview from Vermont.

The first trial has already begun and with the first patient expected to be enrolled on March 19. The trial will test a drug called TPI-287, a new chemotherapy that will be used alone and in combination with other therapies, Sholler said. The idea initially started with the question of “how can we make it so families don’t have to travel so far” for treatment. The doctors who care for these vulnerable young patients also want to focus on treatments with quality of life in mind, which means investigating treatments that are lower in toxicity than traditional therapies while improving their conditions, she said.

Andy Mikulak, Max’s father, is excited about the consortium and what its future success could mean for children who face the same fate as his son. He believes it could nearly double the number of trials available for neuroblastoma patients.

“It’s great for kids. We basically blanketed the U.S,” Mikulak said.

Sholler said she finds inspiration from children facing such difficult battles who, with the love of their families like the Mikulaks, fight the disease with a smile and cheerful outlook.

“It’s such an honor to be able to care for them,” she said.

A key benefit to the consortium is the faith it can give families to carry on in their battles against this devastating pediatric disease, Sholler said.

“I think this going to bring a lot of hope to families…I think it’s needed,” she said.

Sholler said that she admires the Mikulaks’ efforts to continue to look for answers after their son’s death. “It makes my day more meaningful,” she said.

Though he does not work for the consortium, Mikulak, a marketing executive, said he feels a strong connection to those involved because they also participated in the care of his son. “Max was kind of the common link that started their collaboration” he said. Mikulak sees himself as “an advocate connector, who ultimately represents “all the neuroblastoma kids,” he said.

While the alliance is just getting off the ground, there are six other institutions interested in joining the consortium, Roberts said. “There’s this excitement to saying ‘Wow this may be useful’.”

Meanwhile, Mikulak and his wife Melissa have decided to devote their energy to raising awareness about the disease and funding for future clinical trials sponsored by the consortium, he said in a recent interview. They recently formed a charity in their son’s honor called Max’s Ring of Fire and are planning a fundraising event for later this year. The charity is so named because Max loved the song Ring of Fire, especially the version by Social Distortion, said Mikulak, who noted in an email that the ring also symbolizes an interconnected loop of people joining the efforts to find a cure for neuroblastoma.

“It is amazing as we grow this ring, this circle of people touched by Max's story, what has happened so far and what will likely happen,” he said.

Mikulak’s faith in Sholler and her work is based on his experience with her during Max’s most difficult days before his death, he said. She gave him her cell phone number and responded quickly to an email Mikulak sent on one particularly difficult night with Max’s disease.

“She just cares so much about these kids,” Mikulak said. “She is in this thing 24/7.”

It was that dedication and passion plus her dual work as a researcher and a clinician that prompted Mikulak and his wife to decide to focus all their fund raising efforts on promoting her work.

Mikulak was introduced to Sholler through Max who was involved in a phase 1 clinical trial designed to test the safety of nifurtimox that in lab testing appeared to have anti-tumor properties. The antibiotic previously used to treat a child for a parasitic disease known as Chagas appeared to shrink or kill neuroblastoma tumor cells. Sholler’s findings eventually led to the phase 1 clinical trial that included Max as a patient.

A phase 2 clinical trial headed by Sholler is underway in Vermont to further investigate the use of nifurtimox alone or in combination with other drugs as treatment of relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma and medulloblastoma.

Mikulak first became involved in fundraising for neuroblastoma through the Magic Water Project which he cofounded with Neil Hutchinson, another father who has a son with the same disease. The organization is dedicated to funding cancer research on relapsed neuroblastoma and medulloblastoma and funds clinical trials and other research on innovative, low toxicity treatments.

The day after a memorial celebration for Max, a few hundred people participated in a walk in Balboa Park to raise money for the MagicWater Project. Just over $18,000 was collected from the fundraiser, which was sponsored by

RealAge.com , Mikulak’s employer. When plans to fund million dollar scanner a Rady’s Children’s Hospital hit a snag, the money from the walk and other donations totaling $30,000 was instead used to purchase equipment in Dr. Sholler’s research lab, Mikulak said.

Mikulak has since left the Magic Water Project so that he and his wife can devote there fundraising efforts to Max’s Ring of Fire, he said. They started the charity after Max died in part for the same reasons many parents do after their child dies — they want to memorialize their children and the battle they fought, Mikulak said.

“I wanted to tell the story of Max’s battle,” he said.

With the help of a neighbor Max and his wife have filed the paperwork to form their charity. They are in the early stages of planning the charity’s first big fundraiser, dubbed Maxapalooza, for some time in August in what they hope will be an annual event. More information on the couple’s fundraising efforts are chronicled at the new website

http://www.MaxsRingOfFire.org/ .

I've started having "moments" - you know (or maybe you don't), your standing in line at the supermarket when you realize you're going to start crying and nothing can stop the moment.

I've started having "moments" - you know (or maybe you don't), your standing in line at the supermarket when you realize you're going to start crying and nothing can stop the moment. It happens just about every Sunday in church. It's the music really. Sometimes the tune, sometimes the words. They stir me up inside and cause the tears to just flow silently. Standing in the kitchen the other night, the kids eating dinner at the table with Andy, it really hit me how less noise there is in the house without Max. The sounds of three kids interacting was so different. The tears came. I'm not sure if I like this. Of course, what's there to like? I suppose the numbness is starting to wear off. I knew it would. My arm amputation is finally starting to hurt. Unfortunately there are no pain pills for this save tears and heartache.

It happens just about every Sunday in church. It's the music really. Sometimes the tune, sometimes the words. They stir me up inside and cause the tears to just flow silently. Standing in the kitchen the other night, the kids eating dinner at the table with Andy, it really hit me how less noise there is in the house without Max. The sounds of three kids interacting was so different. The tears came. I'm not sure if I like this. Of course, what's there to like? I suppose the numbness is starting to wear off. I knew it would. My arm amputation is finally starting to hurt. Unfortunately there are no pain pills for this save tears and heartache.

The space ended up being great. Very close to what we had originally hoped for. This turn of events on a Monday morn has me feeling great. (Oh – Social D’s Ring of Fire played on the radio on my drive home.)

The space ended up being great. Very close to what we had originally hoped for. This turn of events on a Monday morn has me feeling great. (Oh – Social D’s Ring of Fire played on the radio on my drive home.)